Los sepulcros de Cronos

«La llama está mezclada con el frío… »

de las Metamorfosis de Ovidio al espacio mítico del dibujo.

Carmen Bernárdez

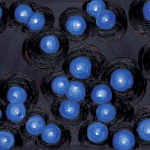

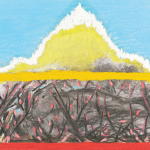

En las tierras templadas de la mitad del mundo recién creado, la llama está mezclada con el frío. Ese lugar, aún tierno, aún sin compactar, tiene el beneficio de la fertilidad del limo y de él surgirán semillas, y será roturado y nacerán criaturas.

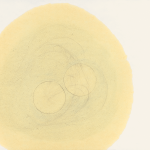

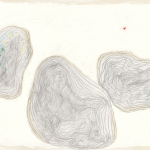

Evaristo Bellotti sabe que también el dibujo es un terreno removido, húmedo y aireado; un lugar todavía caótico que alumbra múltiples maneras de ordenar el mundo, o más bien de ordenarlo para uno mismo. Los trazos primeros de un dibujo son como estacas y cuerdas de agrimensor que miden el suelo y reparten la tierra, origen de la geometría. El dibujante establece esas primeras líneas que sirven de umbrales de acceso a lo que la propia mano sobre la hoja de papel va encontrando con su lápiz.

Hay un dibujo de fundamento que tiene como objetivo la comprensión de las formas. Con él se aprende a mirar viendo, y a describir marcando el terreno con algunas líneas y algunas manchas. Lo que hemos visto, lo reducimos o capturamos con increíble economía de medios: en esas líneas está contenida nuestra sabiduría y la forma del mundo.

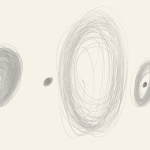

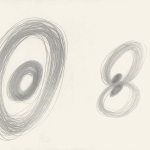

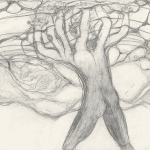

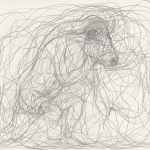

Hay un dibujo soñador que no repara en las cosas que tiene delante. Desinteresado de cualquier aprendizaje, se engancha en su propia magia. El lápiz viaja por la superficie del papel, y en su recorrido descubre e inventaría todo lo que no existe. Respondiendo al grano del papel y a sus fibrillas, salta, gira, presiona su mina. Si es tinta, badea el agua, recreándose en las formas que al secarse adquiere la mancha: como aquellos paisajes de los muros de Leonardo y las nubes de Apolonio de Tiana.

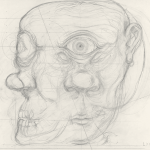

Hay un dibujo de lo mítico que relata historias. Semejante al lenguaje, este dibujo es rico en significados, matices y voces. Semejante a la cartografía, es pródigo en claves, rastros y topografías. Tiene tendencia a superponer sus trazas; a amontonar tanto lo borrado, como lo dudoso y lo seguro de las formas, construyendo un palimpsesto que es un mapa de mapas que registra los titubeos y decisiones, las pérdidas, desintereses y fortunas del dibujante durante el camino.

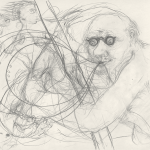

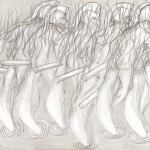

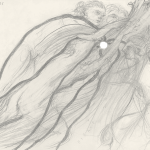

Bellotti dibuja todos los dibujos, pero en esta serie se hace mítico.Tienen esta cualidad cartográfica: sus líneas se multiplican y acumulan, mostrando su urgencia por hallar formas y dejar que ellas mismas se transformen en dibujo. Son líneas vibrátiles que ejecutan transformaciones agitadas como las de Hécuba. Otras veces sus figuras están trazadas –como diría Winckelmann– con la punta de un cabello: así son de finos sus rasgos, como escritura cursiva que vemos en Apolo y Dafne, o en Ganímedes.

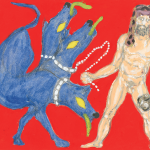

Las historias que cuenta este tipo de dibujo se pueden ver alteradas según el dibujante que, como en el relato mítico, actúa de transmisor oral. Como dicen los mitólogos, es importante que el relato sea el mismo, porque así se preserva la esencia del grupo social. En la repetición fiel del mito se asegura la existencia del hombre: el mito es también ontología. Sin embargo, toda tradición oral imprime variantes significativas. El dibujante Bellotti, como el informador nativo que acompaña al antropólogo, dibuja de nuevo al Minotauro, a Orfeo, a Proteo, como otros muchos han hecho antes, pero su minotauro, su orfeo, su proteo serán siempre diferentes. El mito, sin embargo, queda preservado.

Es cierto que no es lo mismo el mito de origen y significado religioso, que aquel convertido en laico y literario. Sin embargo, tanto uno como otro son fundadores de civilización, porque establecen las condiciones del nacimiento del grupo y la posibilidad de aglutinar a sus miembros. Fundadores legendarios que en el mito grecolatino impregnan de reacciones humanas la peripecia vital de dioses y semidioses. El ser humano, en sus manos, se convierte en objeto de deseo, moneda de cambio, instrumento de venganza, adorno, juguete y pelele de quienes son irremediablemente más fuertes que él.

Las historias de transformaciones que narra Ovidio son relatos completos, cada uno articulado y desarrollado como una historia con otras en su seno. El mito oral que fundamentaba desde lo sobrenatural la existencia del ser humano, es en Ovidio depurada creación literaria. Sin embargo, sabemos que existen otros mitos, sin duda más arcaicos, que se presentan como relatos inconexos, interrumpidos, discontinuos, «fragmentos y remiendos» los llama Levi-Strauss. Es preciso entonces que alguien construya con ellos un tejido, una historia continua.

El dibujo mítico combina ambas posibilidades: ser una historia y ser un fragmento y remiendo. El dibujante parte de hilos sueltos y acaba confeccionando un tejido. De una hoja a las siguientes, cada pasaje elegido y dibujado confiere sentido a la serie, pero cada hoja es en sí un fragmento, un retazo o uno de los varios hilos posibles de la narración. Sorprende que, visualmente, esta imagen fragmentaria pueda estar hecha, cuajada, y funcione separadamente. En el dibujo, historia y fragmento de mito encuentran acomodo y sentido en el valor del lápiz, en un color plano que funciona casi como color heráldico, algo hierático y ajeno a la imposición de la naturaleza. ¿A qué responde la elección de los momentos particulares de cada relato? Son momentos auténticamente preñados de imagen.

El dibujo, podríamos concluir, es un territorio fértil donde se genera mito e historia, no solo formas. Enfrentado a su papel, el dibujante que va a iniciar sus trazos no puede sustraerse a la incertidumbre, pues su dibujo no es servil sino inventivo, y el limo de su suelo de papel, que ha de roturar, puede frustrar su empeño. Esta incertidumbre preserva un aspecto fundamental de la creatividad: no dar nada por sabido, por conocido o dominado. Creer que se está de nuevo en el principio, en un principio. Es tiempo mítico, de suspensión y creemos, con Yves Bonnefoy, en ese inicio del trazo sobre la tela, en el que el pintor tiene aún la oportunidad de reconocerse ignorante y salvar así al mundo…

«The flame is mixed with the cold…»

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses to drawing’s mythical space

Carmen Bernárdez

In the temperate lands of the half of the world recently created, the flame is mixed with the cold. That place, still tender, not yet made compact, has the advantage of the fertility of slime and from it seeds will spring up; it will know the plough and creatures will come forth.

Evaristo Bellotti knows that drawing too is scrambled soil, moist and airy; a place chaotic still, capable of ordering the world in many different ways. Or better still, to order it for oneself. The first traces of a drawing are like the stakes and the rope of a surveyor measuring the land and sharing out the earth: the origin of geometry. The draughtsman establishes those very first lines that are like thresholds to what his own hand will find as the pencil makes contact with the sheet of paper.

There is a foundation type drawing whose aim in the understanding of forms. With it one learns while seeing, learning to describe outlining the land with a few lines and a few stains. Whatever we have seen we reduce it or capture it with an incredible economy of means: in those lines are contained our wisdom and the shape of the world.

There is a dreamer drawing that takes no heed of the things before it. Indifferent to any form of learning, it remains hooked to its own magic. The pencil travels on the paper’s surface, and in the course of its journey discovers what’s there and invents everything that’s not. Reacting to the grain of the paper and all its fibres it hops, spins round, puts pressure on the lead. If it is ink it wades across the water, relishing in the forms that the stain acquires upon drying up, so reminiscent of Leonardo’s walls and the clouds of Apolonio of Tiana.

There is a mythical drawing that tells tales. Not unlike language, this drawing is rich in meanings, nuances and voices. Like cartography, it is extravagant with codes, traces and topographies. It has a tendency to superimpose its pencil marks; to accumulate that which has been erased as much as that which is doubtful or certain of its form, building up a palimpsest that is a map of maps recording the hesitations as well as the decision-making moments, the losses and the disenchantments and the fortunes of the draughtsman along the way.

Bellotti draws all the drawings but in this series he becomes mythical. They have that cartographic quality: its lines multiply and accumulate, showing their urgency to find forms in order to let them transform themselves into drawings. They are vibrating lines carrying out restless transformations not unlike Hecate. Other times its figures are traced –as Wincklemann would say- with the tip of a hair: so fine are their features, like the cursive writing we see in Apollo and Daphne or in Ganymede.

The stories that this type of drawings tell are liable to undergo alterations at the hands of the draughtsman that, as in the mythical tale, acts as oral transmitter. As the mythologists point out, it is important that the tale remains constant since in this manner it preserves the essence of the social group. Man’s existence is guaranteed by the faithful repetition of the myth: the myth is also ontology. However, all oral tradition cannot but introduce significant variations. Bellotti the draughtsman, like the informant accompanying the anthropologist, draws the Minotaur and Orpheus and Proteus anew like many others have done before him but his Minotaur, his Orpheus, his Proteus will always be different. The myth, however, is preserved.

It is true that it is not the same the myth whose origin and significance is religious to that made secular and literary. Both are, however, makers of civilisations in so far as they establish the ideal conditions for the birth of the group and the possibility of bringing its members together. Legendary founders that in Greco-Roman myth imbue the comings and goings of the gods and demigods with human attributes. In his hands the human being becomes an object of desire, exchange currency, instrument of revenge, adornment, toy and poodle of those who are inevitably stronger than him.

The transformation stories told by Ovid are complete tales in themselves, each one articulated and developed as a story containing others in its midst. The oral myth that bolstered from the supernatural the existence of the human being, is in Ovid polished literary creation. We know, however, that there are other even more archaic myths that exist as unrelated tales, interrupted, discontinued, ‘fragments and patches’ as Levi-Strauss called them. It is imperative therefore that someone weaves together a text, a continuous story.

The mythical drawing embraces both possibilities: to be a story as well as a fragment and a patch. The draughtsman starts by handling loose threads and ends up fashioning a fabric. From one page to the next each chosen passage made drawing adds meaning to the series, but each sheet remains a fragment in itself, snippets or just one of the various threads available in the narrative. It is surprising that, visually speaking, this fragmentary image can be satisfactory, gelling perfectly and existing independently. In the drawing, history and myth fragment are lent support and sense by the value of the pencil working on a single colour that functions almost like a heraldic colour, at once hieratical and removed from the dictates of nature. What justifies the choice of given moments within each story? Simply the fact that they are moments literally bursting at the seams with images.

We could conclude that drawing is a fertile ground whence grows not only forms but also myth and history. Coming face to face with his paper, the draughtsman contemplating his first stroke cannot but become prey to uncertainty since his drawing is not servile but inventive, and the slime that is his paper floor –floor that is also ground to be ploughed- can frustrate his endeavour. This uncertainty preserves a key element of creativity: never to take anything for granted, assume to know or be master of anything. To believe one is always at the beginning, at a beginning. In a mythical time, time of discontinuation and suspension and we think, following Yves Bonnefoy, in that beginning of the stroke upon the canvas on which the painter still has the possibility to recognise himself ignorant and thus save the world…